Mitja Tušek

Mitja Tušek

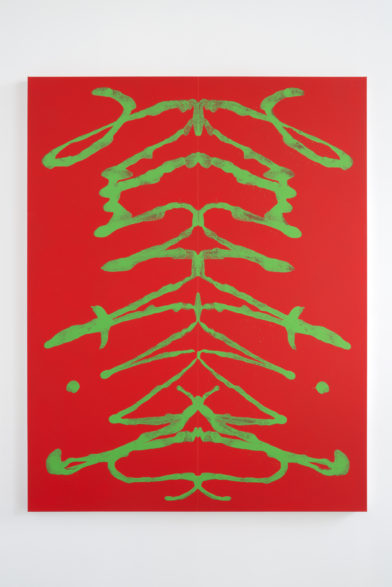

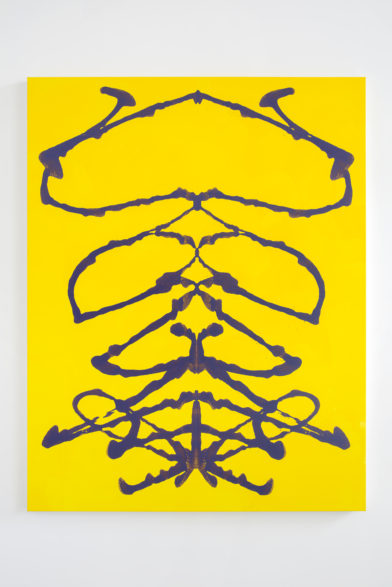

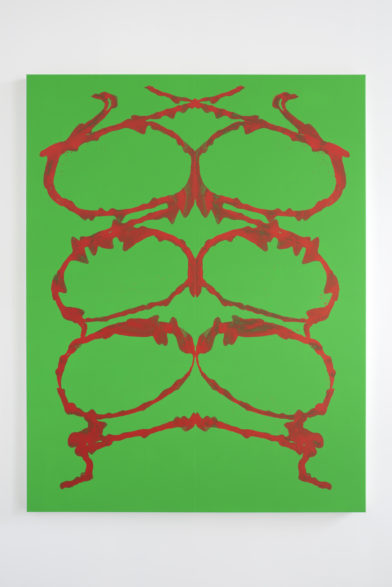

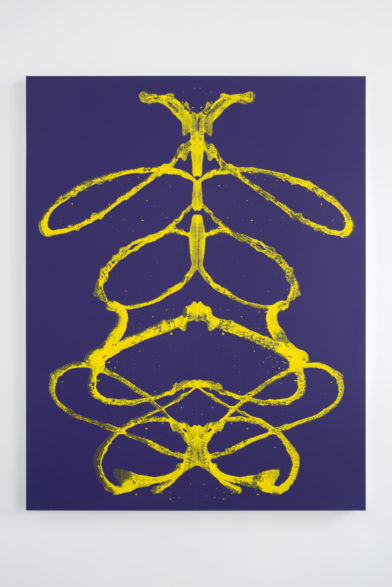

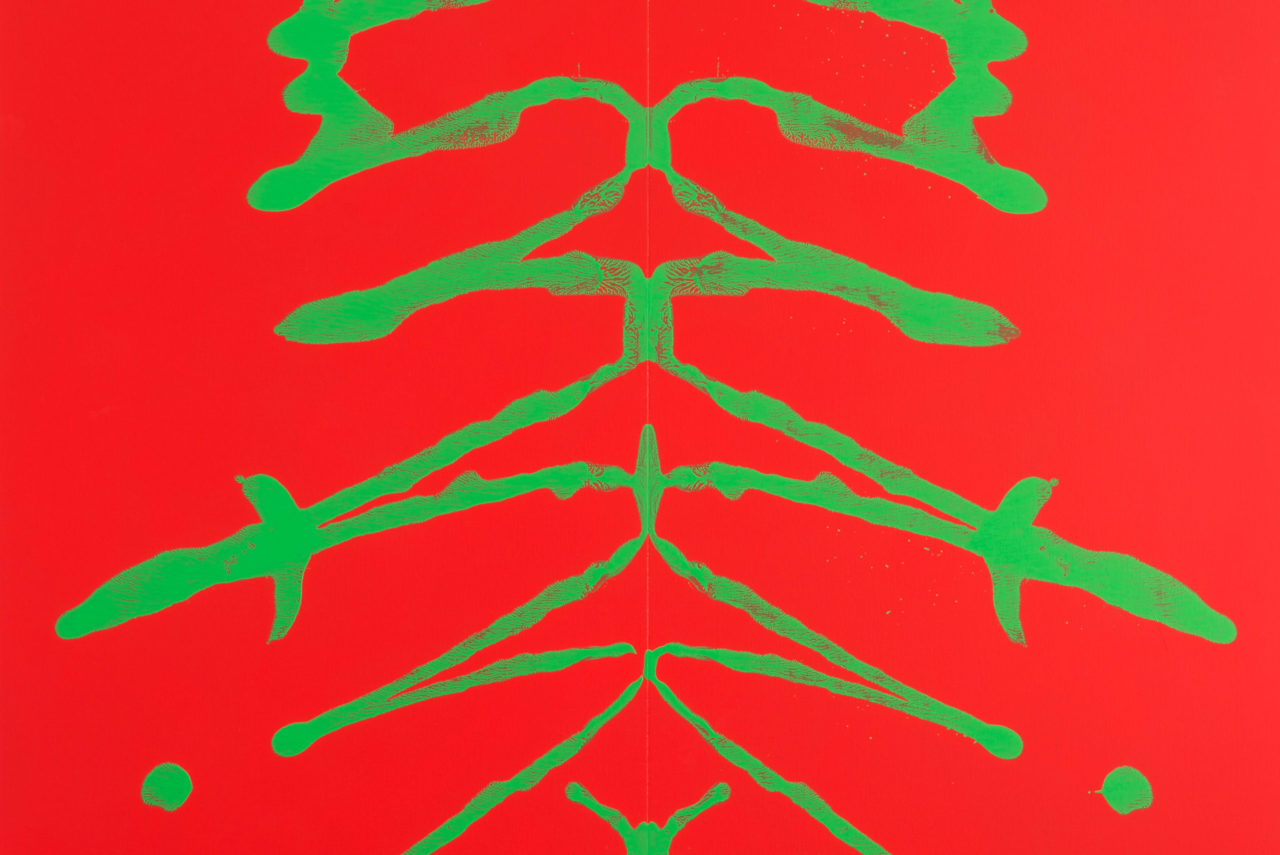

Complementary Colors

1 December 2020 – 30 January 2021 01.12.2020 – 30.01.2021

Rue Isidore Verheyden 2

Baronian Xippas Gallery is pleased to present Complementary Colors, an exhibition of recent paintings by Slovenian-born Swiss artist Mitja Tušek. Mitja Tušek was born in Maribor in 1961 and is now resident in Brussels. He has been exhibiting works since the mid-1980s. His artistic approach involves the exploration of the multiple facets of painting and modernising pictorial genres such as landscape and portrait.

“Cette pondération du vert et du rouge plaît à notre âme”

(This balance of green and red pleases our soul).

Charles Baudelaire, Salon de 1845

The exhibition Complementary Colors occupies two spaces in the Baronian Xippas Gallery that are separated by a public road, the rue de la Concorde. The website of the l’Inventaire du patrimoine architectural de la Région Bruxelles-Capitale tells us that it was originally called rue de l’Union. The existence of a rue de la Discorde (now rue de Venise) was probably the catalyst that prompted the name change in around 1860. Like its topographical location, the exhibition is twofold and contradictory. The works presented in the space on the rue de la Concorde could be grouped under the title Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, and those presented in the space on rue Isidore Verheyden, which bears the name of a painter associated with the XX group, could be grouped under the title Life and Death.

The paintings in the rue de la Concorde evoke groups of individuals. Each painting is a gathering of a small society of faces. These are superimposed, obscuring each other. Each portrait consists of dots of paint sometimes smeared, sometimes simply poured, sometimes spread with a knife. Nine circles in a deep matte black colour, all of different sizes and often overlapping, represent the different elements that make up the face. These circles allude to Dante’s Divine Comedy in which Heaven and Hell are each composed of nine orbs. In Dante’s work these orbs are inhabited by saints and sinners; here, the faces made up of nine circles when viewed in the context of Dante’s orbs, seem, in their singularity, to reveal their own combination of vices and virtues.

Each face has its own skin tone, but it shares common elements with the others, namely the canvas, the same logic, the circles. The biologist Möbius in his study of oysters noted that the framework for a survey should be set for all the species that coexist in a specific space and not for a single species. For a set of living beings coexisting in a given space, the organisation and interactions thereof, Möbius attributed the name of biocenosis. The faces therefore share a given space, the organisation and the interactions thereof. In short, they form a kind of biocenosis, a kind of ecosystem.

Mitja Tušek brings into existence by means of painting heads without bodies, without, however, evoking severed heads. These paintings may look like screenshots from Zoom or Skype meetings, but it’s probably the amount of time spent in front of our screens during lockdown that sparks this interpretation of the paintings that were completed long before the pandemic began. In any case, according to Mitja Tušek, these are indeed paintings of modern life, or perhaps even paintings of wandering souls of modern life.

In the space on rue Isidore Verheyden, Mitja Tušek exhibits a new set of Text Paintings from a series produced in 2009. Entitled Hobbes, this one consists of five solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, short works. The five paintings literally repeat the adjectives with which Thomas Hobbes describes life before the social contract in Leviathan, something that seems to be of relevance to Mitja Tušek still today in 2020. On the subject of the 2009 ensemble of paintings Mitja Tušek says: “I don’t like the 2009 version that much, the colours are a bit stark, and I thought it would be a good idea to produce a more cheerful and positive version of Hobbes. But the intention was for the cheerful version not only to result in more colourful, harmonious paintings, but also to fulfil the promise of Leviathan, a promise of enchantment, which could deserve the adjectives sociable, rich, lovely, spiritual, long.”

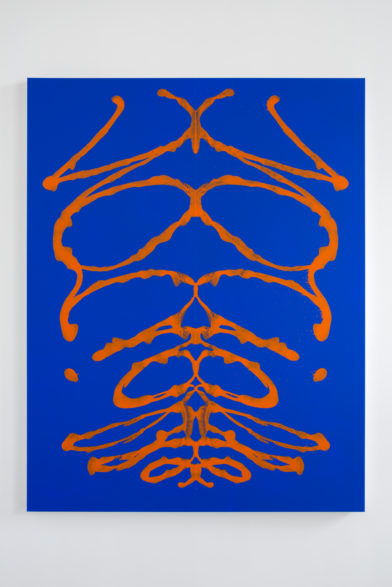

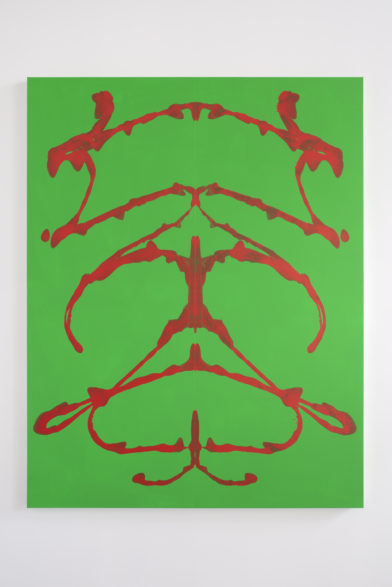

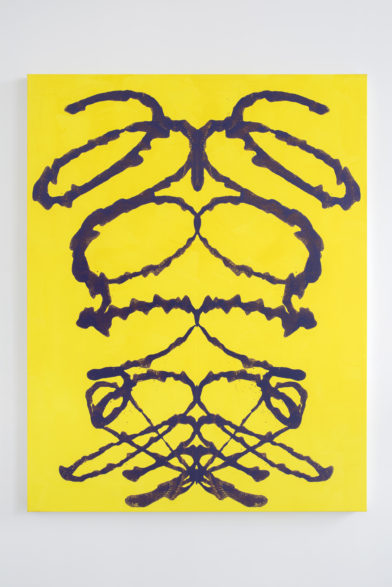

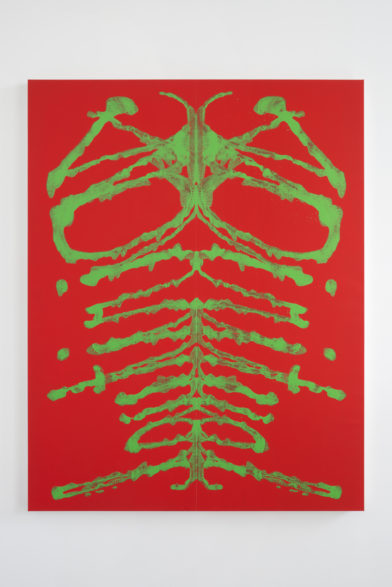

The 2020 version is a playful reading of Hobbes. Confronting the five paintings that qualify Hobbes, is a second series of five paintings by way of speculation. Solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, short, a mischievous contrast with the antonyms: sociable, rich, lovely, spiritual, long. The 2020 version is made up of two ensembles of paintings therefore. Each Hobbes adjective and its antonym are painted with complementary colours, so that nasty and lovely have a yellow background and purple text, poor and rich have a green background and red text. Mitja Tušek happily plays on opposites, scrambling meanings as he scrambles faces in the rue de la Concorde. The painting is very real and watches us.

—

Mitja Tušek was born in 1961 and grew up in Switzerland. He has lived in Brussels for almost 30 years. The subjects he represents are ambiguous: his figurative paintings border on abstraction although we can sometimes find the hint of an image in his abstract compositions. Mitja Tušek works in series (undergrowth, female nudes, Rorschach tests and dark circles) and uses various and varied materials such as oils, acrylics, wax, lead or pearlescent pigments with reflective properties. His work won international appraisal at Jan Hoet’s Documenta 9 in Kassel in 1992, where his paintings were exhibited in the Robbrecht & Daem temporary pavilion. His work has also been shown in many international institutions such as the Kunsthalle in Bern, the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin or The Museum of Modern Art, Oxford.

Artworks and Exhibition Views

Press release

Download the latest press release here